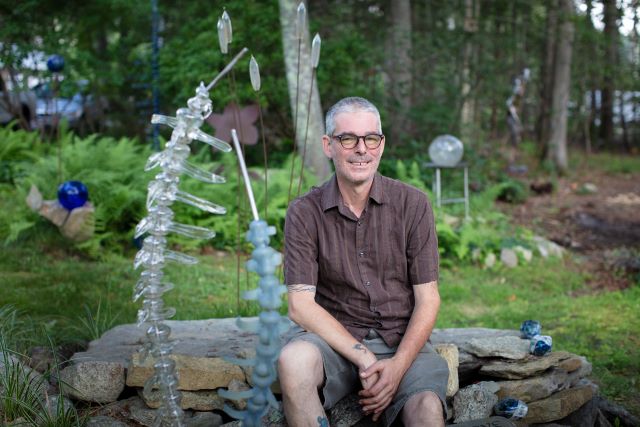

What: Artist in Residence Ian Silvia will be fabricating in metal and stone at Westport Woods in August.

When: Sundays and Mondays, August 13th & 14th, 20th & 21st and 27th & 28th.

Saturday, September 2nd, 4pm: Fabrication demonstrations and concluding presentation

A Little Compton resident, Ian brings a lifetime of familiarity with the local ecosystems to his installations. Below, he responds to questions posed by Merri Cyr of the Westport Cultural Council.

Merri: You are a glass blower and you also use metal and stone. Can you tell us about the materials you work with?

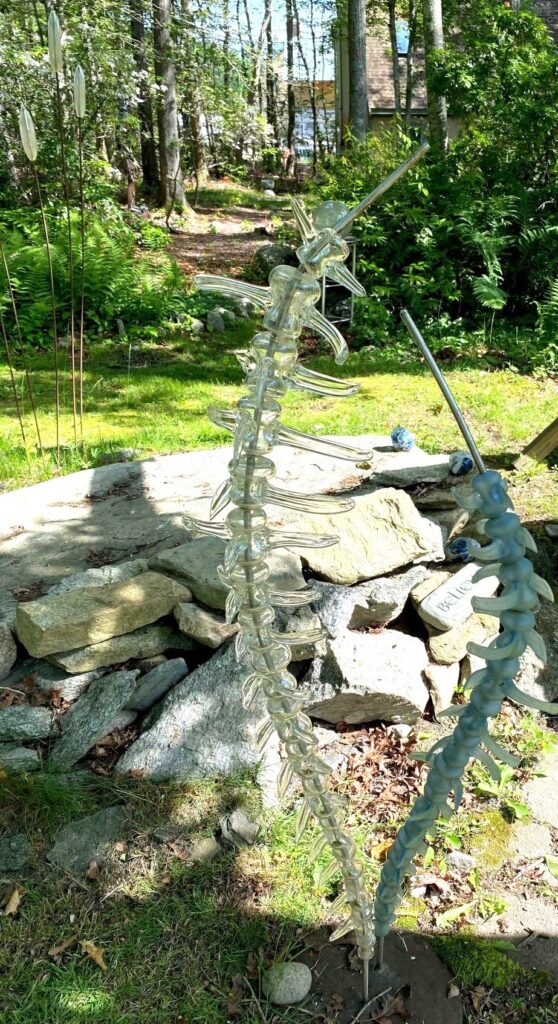

Ian: Stone, metal and glass are materials that have been around for a very long time. I feel like they are materials that have been forgotten over the years with technology, and are traditionally learned about through an apprenticeship program. They’re base materials, they exist in nature already…I always turn to metal and stone because those are also materials that interest me and I feel like they’re part of the same family. I have a connection with them and I feel like I understand them to a certain degree. Those materials have been used for industrialization. Where would we be without glass or metal or stone? They’re also utilitarian materials, but have their own innate beauty…When I’m making a piece out of stone, it’s like I have to find a relationship with it because it’s either going to fight me or it’s going to cooperate. You know, usually I win. Not always, though. And, you know what? It’s the same with glass and metal. I think, can I make you into something?…I am taking them and making them into something that I consider art, but they will always be that raw material. And I’m bound by the rules of that material. I’ve changed what it looks like temporarily, and I think that’s why it’s so attractive, you know? I feel like that in an outdoor public setting that the essence of those materials are always there, we’re just looking at them in a different way.

Working with stone and metal and glass requires planning, sometimes weeks’ long, in order to envision the final product and then work out the steps to make it a reality. It’s more choreography than spontaneity. There’s a thrill when a piece is complete and is what I planned. At the end, that’s where the spontaneity is. You’ve set everything up, envisioning what this piece is going to look like and at the very end, it’s either going to be that or it’s not. And then it’s the make or break moment. When it’s something I made for the first time, it is exhilarating. And you’re going to learn something from those pieces every single time. You know, this is what I want to make. This is my end goal. This is how I’m going to approach it. You kind of follow along with what the glass is telling you. It’s a conversation with the material. That’s what I like about it.

Merri: How did your art adventure start?

Ian: I feel like it started when I was about five years old. My mom went to SMU [now UMass-Dartmouth], to Jimmy Reed, so she would bring me to her painting classes and I would sit there and paint. Later, she did paper quilling–she recreated famous artworks using quilling. Van Gogh was one of her favorites because he had that swirly thing. She was an artist and very unrecognized for her entire life, but that’s kind of where it started.

Merri: Did you think you would be a working artist? At what point did you see it as a potential future?

Ian: I was pretty much involved since high school. But when it came time to decide on college, I was equally divided between cooking school and art school. And I got rejected by both Johnson and Wales and the New York Culinary Institute. They sent me great cookies, by the way, with my rejection letter. I got accepted all the art schools that I applied to and Mass Art seemed the best fit. I entered as an illustration major and I came out with an interest in sculpture and glass. I didn’t even realize glass was a medium until I went to Mass Art and then I saw it being done and I was like, holy crap.

I had always been interested in welding and traditional smithing, but glass really was like a different material. Glass was something that I was unfamiliar with and I didn’t have any idea about. Later I got a job working in Newport at Thames Glass as an assistant, where I started out grinding and polishing.

Doing production work is really like you do the same thing over and over again, but you really learn the material. It’s so different from anything else. That’s sort of what sucked me in. I want to try and do everything, you know?

Merri: You clearly love working with glass.

Ian: We wouldn’t we wouldn’t be a modern society without glass, right? Glass as a material has been around for about 5000 years and blowing glass has been around for 2000 years. It’s a very challenging medium because there’s so many subtleties in manipulating it. There are so many little things that can go wrong with it. I feel like that that’s part of what I like about it.

You start with a very hot blob of molten material and you follow it through to the end product. But there’s a number of rules with glass that you can never break if you want to have an object in the end. The whole process is a matter of cooling and heating while your creating. And then it takes a certain amount of time to cool a piece completely down so it is stress free and it’ll survive. If you’ve done everything right, then you have this piece that you’ve envisioned. You basically make a ton of mistakes and figure out how to fix them. Then you get to that level where you make a whole bunch more mistakes and learn how to fix them.

When I started teaching glassblowing early on in my career, it helped me learn more than anybody ever taught me. When you’re telling people to do something, you have to know what they need to do and why. Glass tends to behave exactly the opposite of other materials, so you have to force learners to forget what they know about other materials. Gravity is a part of it. The process, just balancing the material and having it at a temperature where it wants to work and hold its shape, but yet not break while you’re making it. So it’s it’s challenging in that aspect.

Glass also has a memory. Everything you do to the glass during the process, it’s going to remember that. The only way to erase that is to get it so hot that it loses all form and returns to its molten state. That’s where the challenge comes in. Every time you make a mark on the glass or shape it, you have to balance the temperature between getting it too hot and losing what you did and letting it get too cold and not survive. There’s just so many subtle factors to it. It is basically a permanent substance. You know, my glass will outlive me by a thousand years easily, but it’s also a fragile thing. I’m freezing in time the form that’s in my mind that I’ve created out of a material that is very amorphous, but very substantial. I mean, it is a delicate thing, but it’s also very durable in many ways.

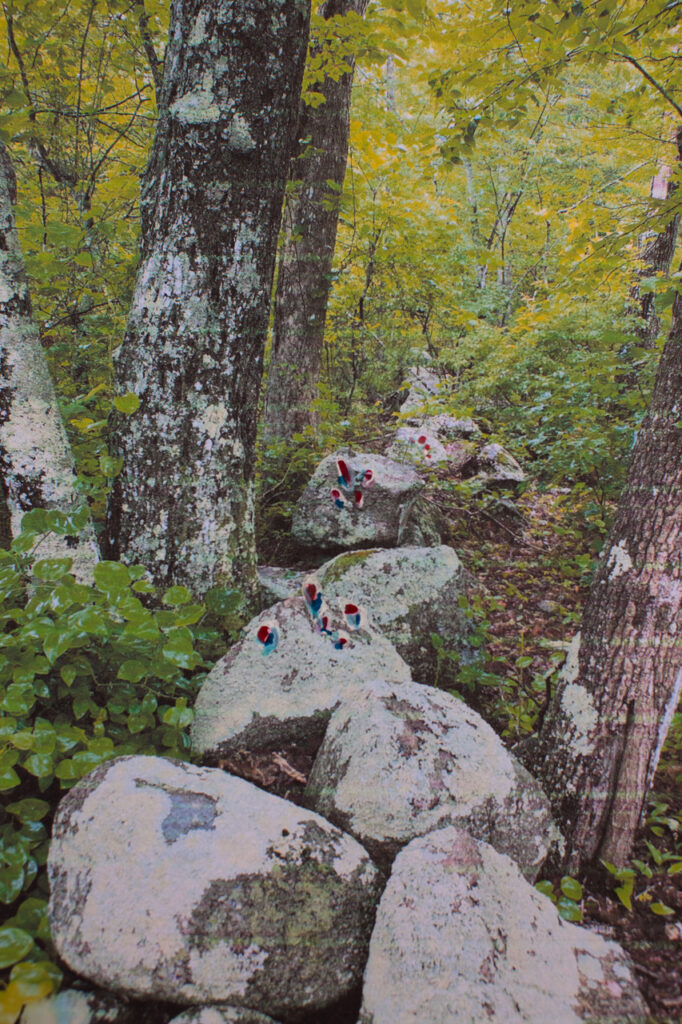

Merri: What draws you to this project–why public art and why Westport Woods Conservation Park?

Ian: I love seeing art any time I travel. I judge the place by the art that I see in public. I think it’s an important thing. It not only reflects humanity, it crosses all boundaries between folks, both rich the poor. That’s why I’m so excited about this project.

As an artist, I want to influence how other people see that space, or I like to put a little bit of humor in my work or something unexpected. Ultimately, we need more of our days changed in a better way. That’s why I think public art has its place because it’s open to everybody. It’s not put into privatized spaces where only certain people can go. Westport Woods attracts so many different people using it in different ways. I think it will be exciting to see their reactions to my art.

The Westport Artists in Residence Program (WARP) at Westport Wood Conservation Park is funded by the Westport Cultural Council (WCC), made possible by the generous support of the Helen Ellis Charitable Trust administered by Bank of America.